"CASTLES OF TERROR"!

"My taste for dead bodies and everything

like mummy is decided." (Vathek)

- The Terror

- The Awful Dr Orlof

- The Castle of the Walking Dead

- The Whip & The Body

- Bluebeard

The "old dark house" has a large precedence in both literature and the visual arts. For centuries ruins have been one of the favourite themes of devotional meditation. It was in the 18th century that these ruins which had appealed to people because of their bizarre disorder were invested with aspirations towards "infinity and the past, towards beauty undermined by death." Those ruins now implied the possibility of sinister developments - since old superstitions believed ruins haunted.

The success of the horror film lies in its invocation of a world to which we are drawn, of the supernatural, of unease. Charles Lamb; "Gorgons, Hydras - may reproduce themselves in the brain of superstition but they were there before. They are transcripts, types - the archetypes are in us and eternal."

Despite our protestations of the triumph of common sense over superstition it is our minds wherein, very deep, are the ancient beliefs and superstitions. The ruins on which we meditate with a mixture of repulsion and attraction are the corridors of the infinite, without end, housing all kinds of delightful horror; the deep caves and subterranean passageways of the inaccessible castles in which Sade's heroes stage their preposterous orgies; and the architectural settings of Piranesi in which all of us "have been Sade once in our dreams"!

Walpole was the first writer to adopt this powerful motif. In his Castle of Otranto the

"lower part of the castle was hollowed into several intricate cloisters... an awful silence reigned throughout those subterranean regions, except now and then some blasts of wind that shook the door she (Isabella) had passed and which grating on the rusty hinges were re-echoed through that long labyrinth of darkness."

ROGER CORMAN’S THE TERROR (1963)

For me

there is a lot of nostalgia wrapped up in The Terror (1963). This is

an American horror film produced and directed by Roger

Corman, and famous for being filmed on leftover film sets from other AIP productions,

including The Haunted Palace. The movie was also released as Lady of the Shadows, The Castle of Terror, and The Haunting.

Corman decided to make the movie to take

advantage of sets left over from The Raven. He paid Leo Gordon $1,600 to write a script, and made a deal

with Boris Karloff to be available for three days filming for a small

amount of money plus a deferred payment of $15,000 that would be paid if the

film earned more than $150,000.

"It is a legendary film that his

its equal share of fans and detractors." writes Alfred

Eaker, "The story behind the film is well known. Corman had finished

shooting The Raven ahead of schedule and still had Karloff

on contract for four days. Not one to waste money, Corman whipped up a

second movie starring the actor. Part of the myth regarding this

film is that it was made in its entirety in 48 hrs. Actually,

Karloff’s scenes were shot in three to four days. Corman utilised the

castle set from the first film, later scenes were added, and the entire movie

was produced over a nine month period, which is something like an epic for

Corman. Corman, of course, masterfully sculpts his own mythology, but

filming commenced without a finished script, and that is probably why it took

so long to pull something halfway saleable out of it. It’s not really an

advisable filmmaking method."

Perhaps not, and The Terror is

certainly not the best of Corman's gothic features. However, there is much to

enjoy: take the opening, Eaker writes, "The opening sequence of Karloff

descending down the castle stairs in the night is stylistically shot. He

opens a door and a skeleton pops out. Animated birds of dread soar

through the credits, enhancing the flavor. Nicely done; except for those

who prefer a coherent narrative, because there is no hidden skeleton in the

film. In this, The Terror is a bit like the pulp comic

book covers which show a potentially exciting scene that never actually occurs

in the story. Not being religiously attached to linear yarn spinning, I

liked the sequence." - I do too, and much besides. Nostalgia rules!

The Awful Dr. ORLOF (1962)

|

ALSO KNOWN AS: |

Until it appeared in the UK as a video (and now DVD) I retained fond memories of "The Demon Doctor" from some long ago flea-pit experience where the impressive black and white photography and old fashioned menace and creepiness left a lingering impression. "Orlof" is a 1962 Spanish–French horror film directed by Jesús Franco. It stars Howard Vernon as the mad Dr. Orlof who wants to repair his disfigured daughter's face with skin grafts from others, with the aid of a slavish blind henchman named Morpho. The film is considered to be the earliest Spanish horror film. One reviewer maintains,

"The Castle of the Walking Dead" (1967)

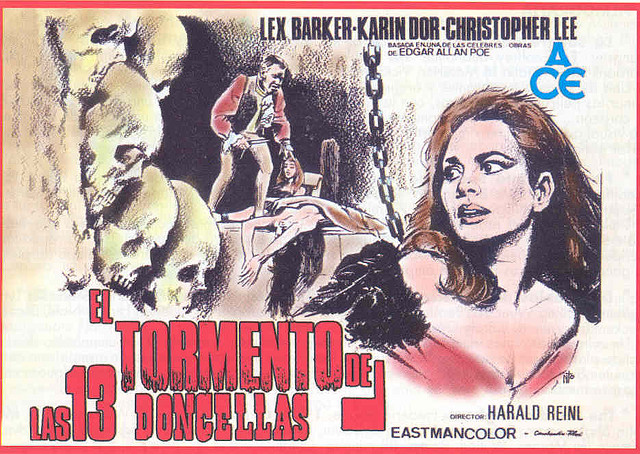

Kevin Nickelson reporting for German Horror Week stated, "Castle of the Walking Dead perfectly embodies the type of wildly florid, tangible artiness that enhances entertainment value in horror films and is sadly lacking in much of today’s output. It’s also a prime example of celluloid that tackles the “If only...” phrase. As in, if only this great-looking film had a script to match."

I caught "Castle of the Walking Dead" (also known as "The Torture Chamber of Dr. Sadism" and

"Blood of the Virgins" amongst other titles!) as part of a seedy double bill at a tiny run-down flea-pit in Bristol where just a heavy curtain divided the tiny theatre from the street and the box-office entrance. Doubtless the cinema is long gone but memories linger on... The film sported its other US title "Blood Demon" and it was billed with "The Faceless Monster" alternatively known as "Nightmare Castle" or "Night of the Doomed" (starring Barbara Steele). In 1969/70 this was a rare opportunity to see something of Euro Horror sleaze which at that time was generally denied audiences in the UK, even those that Britain's prime horror star Christopher Lee had appeared in.

Nickelson likes this film as much as I do and continues, "Castle of the Walking Dead lures the viewer in with a brutal opening sequence involving a spiked mask being forced onto Regula, followed by a lengthy and very disturbing drawn-and-quartering execution. Once the audience is drawn in, the journey through the bizarre begins. The forest that Mont Elise and Brabont traverse through in their trek to the castle, is littered with corpses and body parts jutting out of dead trees. Various color hues are offered here, from a blood-red sunset to dark blue night. The castle, itself, is shown as a crumbling, twisted fortress of death. A mix of gray stone, dirty white cobwebs, and spare torchlight. Numerous paintings, inspired by the works of Hieronymous Bosch and, perhaps, a bit by Salvador Dali, provide an appropriately bizarre air to several castle set-pieces. All of this combines to provide a treasure trove of unique and moodily sumptuous visual treats to keep the film-goer glued."

Nickelson explains, "In the 1960s, while the United States, Great Britain, and even Italy were cornering the market on Gothic horror, West Germany was busy trying to regain a foothold into a style once dominated by Germany, that of expressionistic, wildly visual cinema. The front-running entry in this could very well be 1967’s Castle of the Walking Dead. Directed by Harald Reinl and starring the eclectic trio of Lex Barker, Karin Dor, and Christopher Lee, the film is replete with eye-popping imagery, garish color, and a so-so script that add up to a product that is, if not great cinema, at least perfectly good fare for 3:00am viewing on a Saturday morning."

With touches of gothic menace, a beautiful damsel in distress, mad-lab hocum, and a dash of Poe (elsewhere the film was known as "The Snake Pit and the Pendulum") this minor Euro gem is great fun indeed, and indeed with snatches of film time momentarily redolent of the acme of gothic literature;

"Sometimes I felt the bloated toad, hideous and pampered with the poisonous vapours of the dungeon, dragging his loathsome length across my bosom. Sometimes the quick, cold lizard roused me, leaving his slimy track upon my face..." (Matthew Lewis The Monk)

"The Whip & The Body" (1963)

(Mario Bava, 1963)

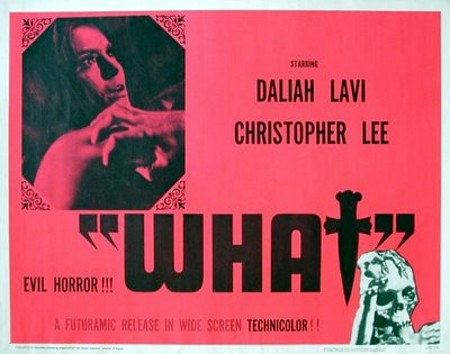

Alternate titles include Night Is The Phantom, The Way of the Body, The Whip and the Flesh, and Son of Satan. A shorter version entitled What! was released in the United States

The Whip and the Body (Italian: La frusta e il corpo) is a 1963 Italian gothic horror film directed by Mario Bava.The story concerns a cruel, domineering man (Christopher Lee) who returns to his castle home and resumes his sado-masochistic relationship with his sister-in-law (Daliah Lavi).

For all Christopher Lee fans with a taste for Gothic Romance The Whip and the Body comes as a pleasant surprise with the advent of DVD and the subsequent release of previously unavailable Euro Horror titles from the sixties, and well worth the wait. This is exceedingly good fare thanks to the welcome presence of a masterful Christopher Lee, the fabulous Daliah Lavi and solid cut-price direction from Mario Bava.

"It was I suppose sadly inevitable", writes Breakfast In The Ruins blogger Ben,"that Bava’s ‘60s classics were often treated pretty shoddily when they found themselves distributed overseas (particularly by AIP in America), falling into a chasm between two eras of horror film-making and not fully emerging until their resurrection as acknowledged classics in the DVD era. Today, Bava’s gothics play out like beautiful reminders of a more elegant era of horror, in which oneiric atmospherics and creeping, devilish unease took precedence over graphic violence and fast-paced thrills. But in the more censorious climate of the early ‘60s, these films’ occasional flashes of lingering sadism and sexuality were deemed beyond the pale by many critics and guardians of decency, a situation probably not helped by AIP’s typically lurid marketing campaigns and English retitling.

All this of course would change only a few years later, when the floodgates of cinematic perversity burst forth into the sleazoid madness of the early ‘70s, but for many of Bava’s best works the tide turned too late, leaving them chopped up, denigrated, critically reviled and all but forgotten in the English-speaking world. As Michael Weldon notes in the entry for ‘Whip And The Body’ in his Psychotronic Encyclopedia, Bava’s films were “treated like cancer” when they appeared in American inner-city theatres, whilst less than ten years later similar but inferior films were regularly being presented as major Hollywood releases."

The Whip & The Body, writes Breakfast In The Ruins blogger, "manages to attain an aesthetic purity and unity of vision that is rarely achieved in the world of low budget commercial cinema, utilising a highly specific visual palette which, together with the flimsy narrative, help to turn it into what is in effect a vast, moving painting.... whether by accident or design, ‘Whip And The Body’ seems to have suffered especially badly from the ill-judged hypocrisy of ‘60s distribution. The film’s suggestions of S&M would have seemed tame stuff even by 1972 standards, but in 1963 the very idea that the beautiful Daliah Lavi is maybe reacting with pleasure as her husband’s caddish brother sets about her with a horsewhip was enough to reduce the film to the most lowly obscurity..."

"If ‘Diabolik’ could be said to be Bava’s great pop-art masterpiece, and ‘Black Sunday’ – at a stretch – his tribute to expressionism, then ‘Whip..’ is more than anything his Pre-Raphaelite showstopper. Full of rich, old world detail and drenched in dense, autumnal colour, it is a film that, appropriate to the gothic tradition, seems to shrug off any suggestion of modernity, drifting instead through a slowly unravelling tableaux of carefully wrought, beautiful things, displayed for us because they are beautiful, and because we, the movie-going connoisseurs of such things, deserve the opportunity to drink them in at our leisure."

Reviewer Timothy Young writes, "The fascinating script more than outweighs its few flaws and although slightly gratuitous, the sadosexual whipping theme provides a very unusual atmosphere. Some solid direction and a strong cast serve to make this one of the most original and enjoyable gothic horrors to emerge from Italy during the decade."

Reviewer Timothy Young writes, "The fascinating script more than outweighs its few flaws and although slightly gratuitous, the sadosexual whipping theme provides a very unusual atmosphere. Some solid direction and a strong cast serve to make this one of the most original and enjoyable gothic horrors to emerge from Italy during the decade."

"Released in the United States in a heavily censored edition that eliminates all traces of sexual masochims, LA FRUSTA proved to be quite ahead of its time. In retrospect, the American title WHAT! pretty well sums up the reactions of audiences at the time, baffled as they must have been by the incomprehensible re-editing." (Troy Howarth)

BLUEBEARD (20o9)

Barbe Bleue directed by Catherine Breillat

Barbe Bleue directed by Catherine Breillat

Bluebeard is the great-granddaddy of all

"old dark house" stories. It is a French literary folktale, the most famous surviving version of which was written by Charles Perrault and first published by Barbin in Paris

Bluebeard (French: Barbe Bleue) is a 2009 French film directed by Catherine Breillat. Critic Phillip French has written: "Catherine Breillat sets aside her characteristic dans ton visage eroticism, but clings to her usual feminism to retell with crisp dispatch Perrault's blood-curdling, much-analysed fairy tale of how a medieval virgin did for the serial uxoricide, Barbe Bleue.

Breillat's tactic is to have the story read in a cosy attic in a modern French chateau by an eight-year-old girl (by implication Breillat herself) to her slightly older sister as a way of terrifying her. An interesting conceit, a clever film but somewhat perfunctory and altogether less interesting than, for instance, Neil Jordan and Angela Carter's The Company of Wolves."

However, the film found favour with New York Times critic Manohla Dargis who wrote; “Bluebeard” suits Ms. Breillat, who likes to mix the blunt in with the oblique..." and continues, "the movie is at once direct, complex and peculiar... The little girls are naturals and the dusty attic in which they read and play looks genuine enough to sneeze at. Not so the actors in the Bluebeard section, who move in period costumes through minimalist sets that have little of the sumptuous detail that tends to characterise more mainstream and costly efforts of this type. There’s a stripped-down quality to these trappings, which might be a function of budgetary constraints but also complements Ms. Breillat’s analytic approach, the critical distance she sometimes likes to assume. The sets, the clothes, the telegraphed performances — actors recite lines that sound like lines — along with the intermittent annotations from the little girls, remind you that you’re watching a self-conscious fiction, one that generations have preserved and recast."

.jpg)